ELISA ODDONE

Photojournalist

“Employers want money to fill the papers needed for the regularization. A person asked me for €1,500 ($1,716), another one €1,200, and a last one €1,050. But I don’t have this money. Bribes are much higher in the north, a friend of mine who lives in Rho, near Milan, was asked to pay €5,000.”

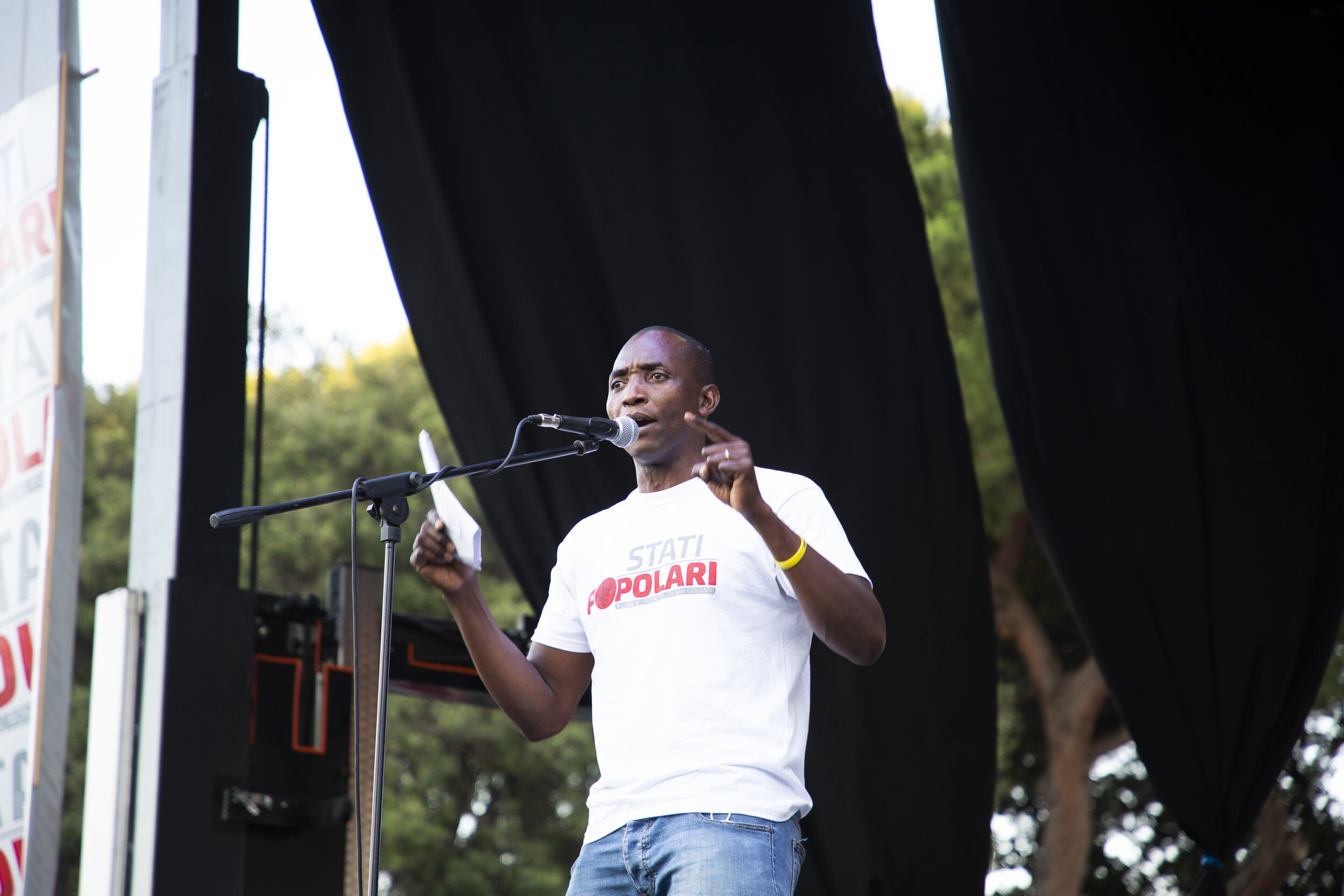

Milan-Rome-Matera — Moses Isaac Osazuwa is a 41-year-old farmer from Nigeria's southern Edo state. He reached Italy's island of Lampedusa by boat in 2012, after fleeing a Libyan prison as the country plunged into war.

Back home, Osazuwa was a farmer and a member of a local political party, which managed to win a provincial election back in 2010. But the joy was short-lived. Riots ensued and the opposition party took over.

"I'd be dead if I didn't escape," he says.

Once in Italy, Osazuwa quickly found a regular farming job in the southern province of Matera that lasted until 2017. From then on, he began living off occasional jobs.

The farmer thought things could change for the better when the government launched a procedure for the "emersion of work relationships" on June 1. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the decree was thought to offer a pathway to legalization for those working in agriculture or as domestic helpers across the country.The farmer thought things could change for the better when the government launched a procedure for the "emersion of work relationships" on June 1. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the decree was thought to offer a pathway to legalization for those working in agriculture or as domestic helpers across the country.

When his papers given on humanitarian grounds expired in February last year, the territorial commission didn't renew them, deeming his case not suitable to receive further protection.

But Osazuwa's hopes faltered when he found himself victim to blackmailing.

"Employers want money to fill the papers needed for the regularization," he says. "A person asked me for €1,500 ($1,716), another one €1,200, and a last one €1,050. But I don't have this money. Bribes are much higher in the north, a friend of mine who lives in Rho, near Milan, was asked to pay €5,000."

Announced with much fanfare, the decree aimed to grant permits to at least 200,000 undocumented migrants working in agriculture, a sector brought to its knees during the pandemic due to a shortage of workforce available, which used to come mostly from Eastern Europe. Granting legal status was supposed to prevent workers' exploitation.

But the reality on the ground is much different.